The community model transforming social protection in Cambodia

It really does take a village to protect a child

Lire cet article en français:

N.B: Si vous souhaitez recevoir directement les articles en français de The Fifth Wave Institute, vous pouvez vous désabonner de la newsletter principale et vous abonner à celle en français en vous rendant sur fifthwaveinstitute.com dans la rubrique ‘Gérer mon abonnement’.

A major transformation is taking shape in Cambodia’s social care system. What started as a grassroots effort to stop children from being put into orphanages is now being scaled nationwide as the blueprint for social protection — thanks to one community model revolutionising the country’s approach to care.

What should a society do when families are unable to care for their children?

For decades, the default answer was orphanages — residential institutions where children without parental care are looked after by staff. However, as evidence mounted that orphanages do more harm than good to children’s well-being, many countries moved beyond the orphanage model, opting instead for foster, family- and community-based systems to house and care for vulnerable children.

In countries with underdeveloped social support systems, though, charity-run orphanages remained a prevailing solution. And in Cambodia, where about one in six people live below the poverty line, families who couldn’t provide their children with adequate food, healthcare, or education turned to orphanages as a last resort. This is why 80% of children living in Cambodian orphanages are not actually orphans, but children whose families felt they couldn’t afford to care for them1.

A care system in crisis

In the early 2010s, Cambodian orphanages came under fire. Emboldened by the growing demand for “orphanage tourism”, it became obvious that many had been abusing and exploiting children for profit.

Orphanage or ‘volontourism’ emerged in the 2000s as an increasingly popular form of tourism in developing countries. Seduced by the promises of white saviourism, wealthy tourists and young international volunteers would visit orphanages for a “feel-good” travel experience, unaware of – or undisturbed by – the fact they were helping to create an “orphan-industrial complex”2.

Between 2005 and 2015, the number of orphanages in Cambodia increased by more than 60%. Children were often “recruited [or] trafficked to fulfil the demand for ‘orphans’”3, and purposefully “kept in poor health, poor conditions and malnourished in order to elicit more support in the form of donations and gifts”. Once supposedly an institution of care for vulnerable children, Cambodian orphanages had become a profit-generating machine, with children the commodity being sold4.

Recognising what had now burgeoned into a full-blown crisis, the Cambodian government made a public commitment in 2017 to shut down all their orphanages and shift to a family- and community-based care model.

However, until recently, those efforts had largely failed. Critics argued that the solution was a cosmetic one: it didn’t address the social realities at the root of why children end up in orphanages in the first place. Forcing their closure with no formal protection system in place to ensure children’s safety going forward meant many would merely return to a life of poverty – putting them at further risk of trafficking, child labour, underage marriage, and other forms of abuse and exploitation5.

But in June 2025, that changed. Inspired by a grassroots social protection initiative developed in the northwestern province of Battambang, the Cambodian government finally took steps to address these root issues when they adopted the Village Hive Model as their national child protection framework.

The model

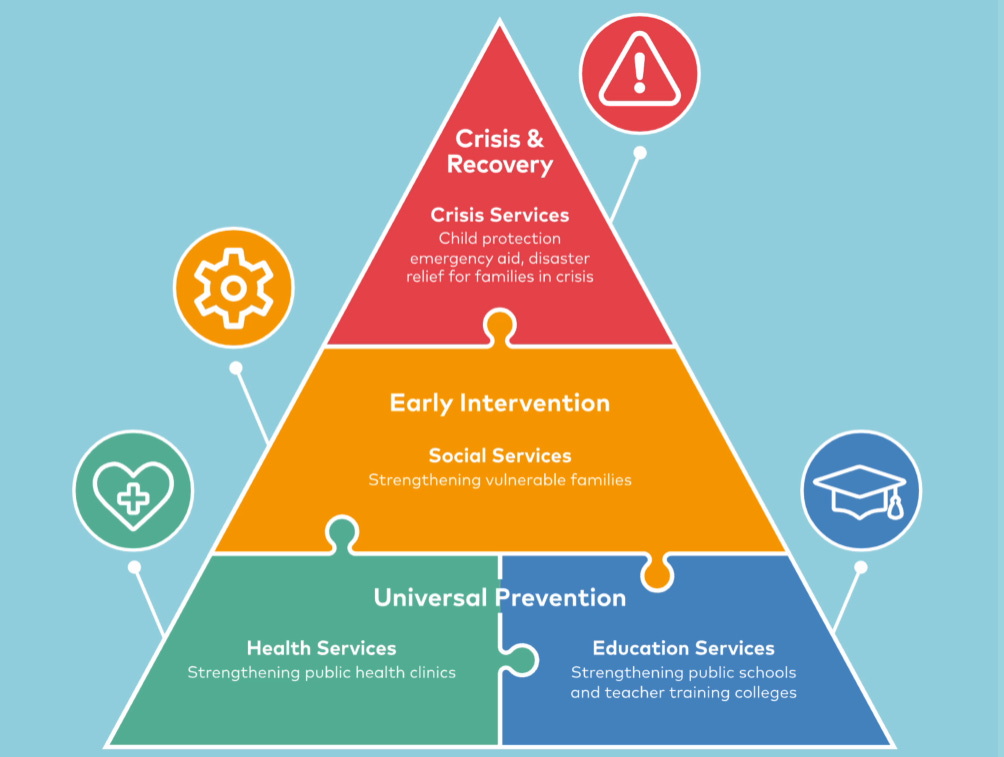

Kickstarted by Cambodian Children’s Trust (CCT), a local orphanage-turned-NGO, the Village Hive Model offers a groundbreaking framework for a community-led social protection system. The three-tiered, upstream model works to eradicate both poverty and local dependence on charity.

Tier 1: Universal prevention

The foundation of the Hives is the strengthening of public services, like schools and health clinics, to ensure universal access. These essential services raise well-being and living standards for every family in the village.

To prioritise community agency, the programme challenged school and clinic staff to identify their own strengths and needs. CCT’s role then became primarily to supply what they asked for — a non-directive approach rare amongst NGOs.

The Hives invest in public health infrastructure by stocking up on essential supplies, ensuring clean, functioning, and accessible facilities. They provide health workers with additional staff and training opportunities. Local health centres are then better equipped to prevent disease and manage acute and chronic conditions when they arise.

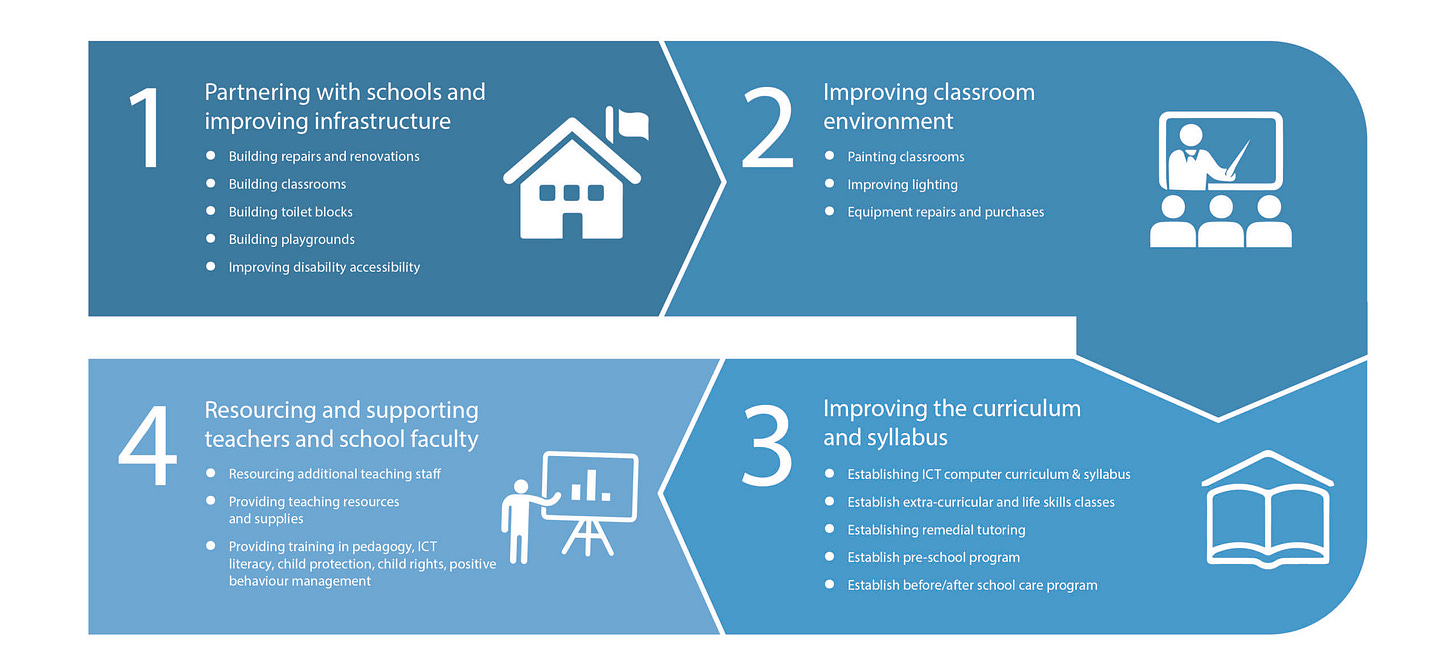

Within schools, the Hives ensure that facilities and curriculums are accessible and of high quality. They provide teachers with additional staffing support, supplies, and training in pedagogy, ICT literacy6, child protection, child rights, and positive behaviour management.

Furthermore, the model provides opportunities for students to participate in extra-curricular activities, life skills classes, remedial tutoring, and more. These efforts create a public school system that helps every child learn and thrive in a safe, nurturing, and stimulating environment.

Together, the strengthening and universalising of these essential services are designed to set children, families, and communities up for success for years to come.

Tier 2: Early intervention

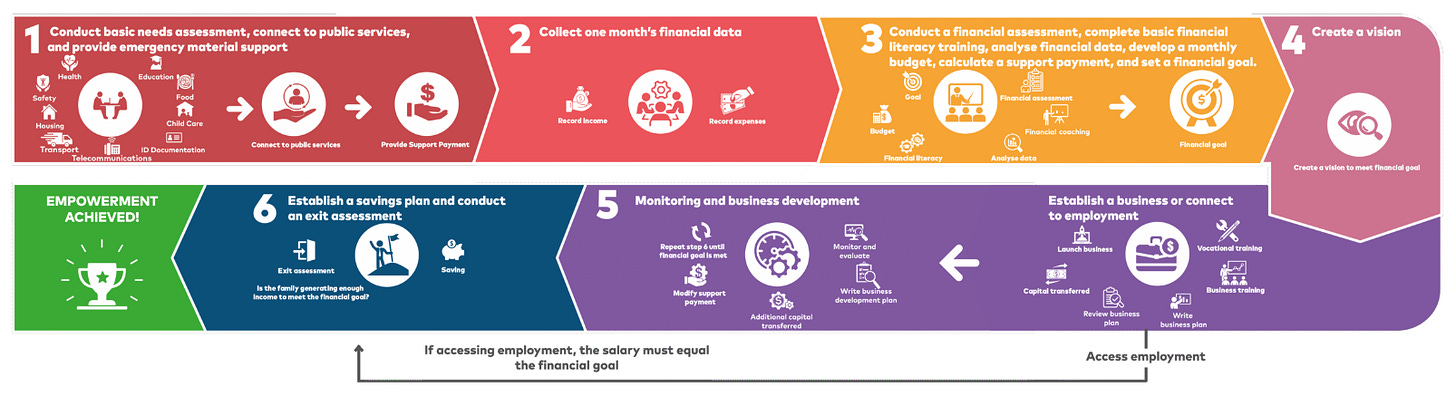

Once basic public services are in place, the Hives’ early intervention scheme attempts to anticipate crises by tackling poverty at its core. Social workers are referred to at-risk families, who they guide through a six-step journey to financial independence.

Outlined in the graph below, that journey starts with conducting a full audit of the family’s basic needs, as well as their monthly income and expenses. This helps connect each family to appropriate public services, design them a financial literacy training and budget, calculate a support payment, and help them set a financial goal.

The social workers then work with families to build a business plan or connect them to employment, and continue monitoring and supporting them to help them reach their goals.

Poverty is a root cause of many issues facing local communities, including family separation, child labour, and trafficking. The support provided to these families equips them with the tools they need to shift their focus from day-to-day survival towards long-term stability. When families gain financial literacy and independence, they become less reliant on charities and are better able to support their children, ultimately decreasing the likelihood of these children falling into exploitative situations.

Tier 3: Crisis response

With prevention and early intervention systems in place, fewer families reach a point of crisis. This means response services are no longer overburdened, allowing them to deliver care more effectively to those in need.

When a crisis does arise, such as reports of abuse, neglect, family separation, child labour, or trafficking, the Hives are equipped with a range of services to address the issue and offer safe alternatives. These include a 24/7 emergency hotline, counselling, crisis housing, kinship care, care leaver support7, family reintegration, addiction support groups, and disaster relief.

When social workers determine that a child can’t safely be cared for by their parents, they work with the extended family network to find other options, prioritising placing the children with family and friends they feel comfortable with before resorting to foster care. They support carers with child protection training and financial support to ensure they are well equipped to provide a safe and nurturing home for the child. They also offer counselling to the child and family to help them work through their challenges.

With this multi-layered and interlocking network of social protection, the Village Hives work to systematically ensure no more children end up in institutional care — providing a blueprint for what truly effective community-based social support can look like8.

Empowering communities

The process of building the Hives began with ‘co-creation workshops’ in each target community. These brought in the voices of local leaders, public servants, and other stakeholders to identify local child protection issues and brainstorm potential solutions. Since this initial ideation, co-design workshops have continued to inform the evolution of the Village Hives.

“I’ve never seen another NGO work like CCT. The Village Hive is as pioneering as the astronauts on the Apollo mission”, said Hak Chanley, Deputy Head of the Cambodian Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans, and Youth (MoSVY). “I saw the commune chiefs, local leaders, government and CCT working so well together. Everyone has the same goal [...], supporting families who have problems until there are none.”

This ability to drive and define their own solutions is one that Cambodian communities have routinely been deprived of. When the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime effectively demolished the country’s care infrastructure in the 1970s, international NGOs stepped in to fill the gaps. Though most of these organisations had good intentions, they created a national care system that depended on foreign charities to deliver essential services.

For decades, this cycle of dependency has deprived locals of empowerment and leadership opportunities, making them reliant on foreign actors to define their issues and prescribe solutions. And sadly, those were rarely rooted in local context and long-term sustainability.

“We want to start a movement to shift power from NGOs back to local communities,” said Pon Jedtha, CCT co-founder and Country Director. “Instead of all the NGOs working in the private sector, which they have full control over, we want to see [them] work within the public sector, using their donations and philanthropy from around the world to invest in building universal public services and trusting communities to do this work.”

CCT’s path towards “breaking the cycle of charity” has not been straightforward. In fact, Pon Jedtha and co-founder Tara Winkler initially developed CCT itself as an orphanage in 2007, before undergoing a restructuring when they realised that most children ending up in their care were not actually orphans. Since then, the organisation has only continued to learn and adapt to what local communities actually need to thrive.

“In 2019, we realised we had hit a dead end. If CCT continued down the same path we were on, Battambang would be dependent on us delivering essential services forever,” said Jedtha. “We deserve a community that can stand on its own and care for its people. Our children, and our children’s children, should grow up knowing the safety of a well-resourced community.”

Working themselves out of a job

This realisation is precisely why one of the organisation’s core tenets is its exit strategy.

It’s a paradox many nonprofits face: if they actually solve the problems they set out to solve, they render themselves redundant. While many organisations shy away from this reality, CCT has made obsolescence central to its mission. As Winkler explains:

“The international development sector was built on a mindset of empire-building, where organisations grow their own brands, programs and infrastructure that they operate privately in parallel to public systems. Shifting to a deeper, more humble focus on solving the root causes of problems in the Global South requires that those same organisations let go of the structures that keep their own names alive.

That’s uncomfortable, because it means losing the ability to stake a claim and say: ‘This is our school, our centre, our program.’ Yet that loss of ownership is precisely the point. When projects blend seamlessly into public systems, the logo may fade, but what remains is far more powerful: a lasting solution owned by the community itself.”

CCT hopes to ‘work themselves out of a job’ by 2032, made redundant by fully functional and self-sustaining Village Hives. This would mean that communities have taken complete charge of their own social protection services, successfully tackling issues as they arise and implementing ongoing, locally driven and informed solutions.

And they’re well on their way. To prioritise localisation, CCT has shifted to a fully Khmer leadership team and implemented an affirmative action policy that ensures equal pay between local and expatriate employees. This policy also stipulates that CCT can only hire expatriates if there is demonstrable proof that their expertise is not available in Cambodia9. As a result, there have been no expat employees at CCT for the past five years.

Since their launch in 2019, the Village Hives have had an enormous impact. According to CCT’s data, families have been shown to increase their income by 142%, reduce their debt by 61%, and continue thriving independently even after completing the early intervention journey10.

As of 2024, the Hives were supporting over 50,000 people across three communes and 18 villages in Battambang province. CCT plans to have the district’s ten communes and 62 villages fully integrated by 2032. And with the model now being adopted by the national government, its scale and impact are only going to keep growing.

“We plan to expand the Village Hive to all 25 Cambodian provinces and the capital city,” explained Siem Sopheak Votey, Family Affairs Director within MoSVY. “We want provincial, commune, and NGO partners to implement [it] together to create one cohesive system to address the root causes of poverty.”

Rebuilding trust

One of the most common concerns about shifting towards a community-based model and integrating the Hives into the public system is about government corruption. In 2024, Cambodia ranked 158 out of 180 countries in the Corruption Perceptions Index, making its corruption issue amongst the worst in the world. Because of this, a lot of foreign trust has been lost in the country’s public institutions.

Sustainable, publicly-integrated Hives require complete trust and cooperation between all its stakeholders. This is why the Hives tackle corruption head-on to rebuild this trust. They’ve implemented strict anti-corruption policies and procedures, requiring regular reporting, training, and discussion forums to evaluate progress and brainstorm solutions11.

“There’s a deeply entrenched idea that communities in the Global South can’t be trusted to run their own affairs. But corruption isn’t an insurmountable problem — it’s not [inherent to] the culture or character of the people. Corruption is simply a symptom of a flawed system,” said Tara Winkler. “We are proving that with the right checks, controls and transparency, we can overcome concerns of corruption.”

These efforts are ongoing, but most participants report that they are already proving effective in ensuring accountability and preventing corruption. Local leaders are also reporting a better functioning relationship between governments and communities.

“[The Village Hive] has promoted inclusivity and encouraged greater engagement between the community and local government,” said Chea Vibol, from Ou Char’s Commune Council. “Local governments have become more responsive to community needs, actively listening to feedback and making fair, impartial decisions that reflect the best interests of our people.”

Funding systems change

While corruption is a major concern, it’s not CCT’s only barrier to securing funding for the Hives. The organisation has found that their project’s complex and long-term nature often confuses donors, who are usually more attracted to clear visions and immediate results.

“Systems change work takes time, and it is not always easy to explain. It was much easier for CCT to raise funds when we were an orphanage!”, Keir Drinnan, Managing Director of CCT Australia – a branch that provides financial and strategic support to the Hives – told me.

As an NGO, CCT has historically mobilised international donors to raise much of the money needed for their projects. However, creating sustainable, publicly-integrated Hives ultimately requires financial backing from the state — and that has often proved difficult to come by. “A lack of understanding by the general public about the upstream approach that CCT is working on”12 can make it challenging to get communities on board and pitch the project to government officials, who might struggle to see the vision the Hive is working towards.

But CCT carries on demonstrating the model’s evidence-based impact. To them, self-sustaining communities where each member receives the care they need to thrive is a vision worth fighting for. And despite initial challenges, the Cambodian government is now contributing their own funding to the project, marking a major step towards the Hives’ sustainability — and CCT’s dissolution.

Globalising localisation?

Localisation is at the heart of the Hives. Their very essence is to be built by Cambodians, for Cambodians. But this doesn’t mean that their community-driven framework is not applicable in other cultural contexts. For CCT, localisation must be the basis of any systems change.

“At its core, localisation should be a matter of power — who is in control and who is making the decisions,” said Winkler. “Power never truly shifts if it remains within the orbit of foreign-controlled NGOs and donors. The only way to create lasting change is to build robust social welfare services within the public system, where the roots of control are inherently local.”

So, while the Hives’ specific characteristics may not work anywhere, its core tenets can.

The Village Hives conceptualise care as a deeply communal, shared responsibility; a process of co-creation and co-evolution. Theirs is a complex, interconnected system of protection which acknowledges that the issues our care systems attempt to fix are mutually inextricable, and thus require a holistic approach.

The model shows that far from a saviour gallantly swooping in to save someone in crisis, effective care systems work outwards from the core. Systems where each member not only has their immediate needs met, but is set up to continue flourishing for decades to come, require the active involvement of communities.

On a global scale, this means communities have power — from the grassroots, village level all the way up to the national policy level. Governments and NGOs need to trust and support them to drive their own change.

And as for each of us, it means we carry a responsibility to ground our practice of care within our own communities, in our daily interactions, as a precondition for building anything else.

Miller, A., & Beazley, H. (2021). ‘We have to make the tourists happy’; orphanage tourism in Siem Reap, Cambodia through the children’s own voices. Children’s Geographies, 20(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1913481.

All information in this paragraph taken from: Higgins-Desbiolles, F., Scheyvens, R. A., & Bhatia, B. (2022). Decolonising Tourism and Development: From Orphanage Tourism to Community Empowerment in Cambodia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(12), 2788–2808. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2039678.

Miller & Beazley, 2021.

Aside from footnote 2, all other information in this paragraph is taken from Higgins-Desbiolles et al. (see above).

Ibid.

Information and communication technology.

For children typically aged 16 to 25 leaving foster care.

This information about the Village Hives are taken from CCT’s website. To learn more, visit Village Hive (2024) - Cambodian Children’s Trust.

Mona Nikidehaghani and Freda Hui-Truscott, 2024. Localisation of Humanitarian Aid: A Case Study of Sustainable Development in Cambodia. AABFJ Volume 18, Issue 1.

Numbers listed on CCT’s website, at https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/village-hive/. Retrieved 29 December 2025. A study by Charles Darwin University is currently underway to independently evaluate the Hive’s impact on communities.

More information about the way CCT is handling corruption can be found on CCT’s website: The Process - Cambodian Children’s Trust.

Hui-Truscott, F., & Nikidehaghani, M. (2024). Evaluating the localisation of the Village Hive Project: A Case Study in Cambodia. Wollongong; University of Wollongong Australia.