Last year, Mexico’s president Claudia Sheinbaum introduced a new national pension for women aged 60 to 64, in recognition of the unpaid care work they have done and continue to do. More than a million women aged 63-64 already receive it, and the government recently announced its imminent rollout for the second half of women.

The provision comes as a gender-specific complement to the existing universal pension for those aged 65+, established by former president Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador (known as AMLO) in 2001. Both are non-contributory, bimonthly cash transfers, meaning they aren’t conditioned to prior labour market contributions. The ‘Women’s Well-Being Pension’ (Pensión Mujeres Bienestar) comes at about half (3,000 pesos, roughly $160) of the national pension’s 6,200 pesos.

In her press conference announcing the policy, Sheinbaum delivered words rarely pronounced by a head of state:1

“One of the reasons we’re supporting women aged 60-64 is that not only did they take care of their children, they are now taking care of their grandchildren, and they should have economic support. Many of them don’t have a proper revenue, they have no economic independence: they will now receive support from the government so they at least have some resources for themselves.”

She then lamented the use of the term ‘ama de casa’ (homemaker) in a pejorative sense, claiming “I am a president, a grandmother, a mum and a homemaker, and with pride. So to all those who think ‘homemaker’ is an insult, I say no. We’re going to take charge, as women, to recognise the work done by so many women in the home”. She rejected the devaluation of housework, constitutive of a “macho culture”2.

Like a lot of recent policy decisions in Mexico, this is bold and exciting. The unconditional aspect is particularly interesting: it takes for granted that all women have done some amount of care work, and therefore deserve compensation. No further questions asked.

There is an ongoing debate about the potential (or lack thereof) female political leadership holds for changing the culture around care. I would just like to say: exhibit A. Women like Sheinbaum who ‘lean in’ and ‘climb to the top’ (quite literally, to the highest office in the land) can also use their position to make everyday life easier for everyday women, while at the same time openly acknowledging and valuing the place of care in their own lives.

Care pensions in the world

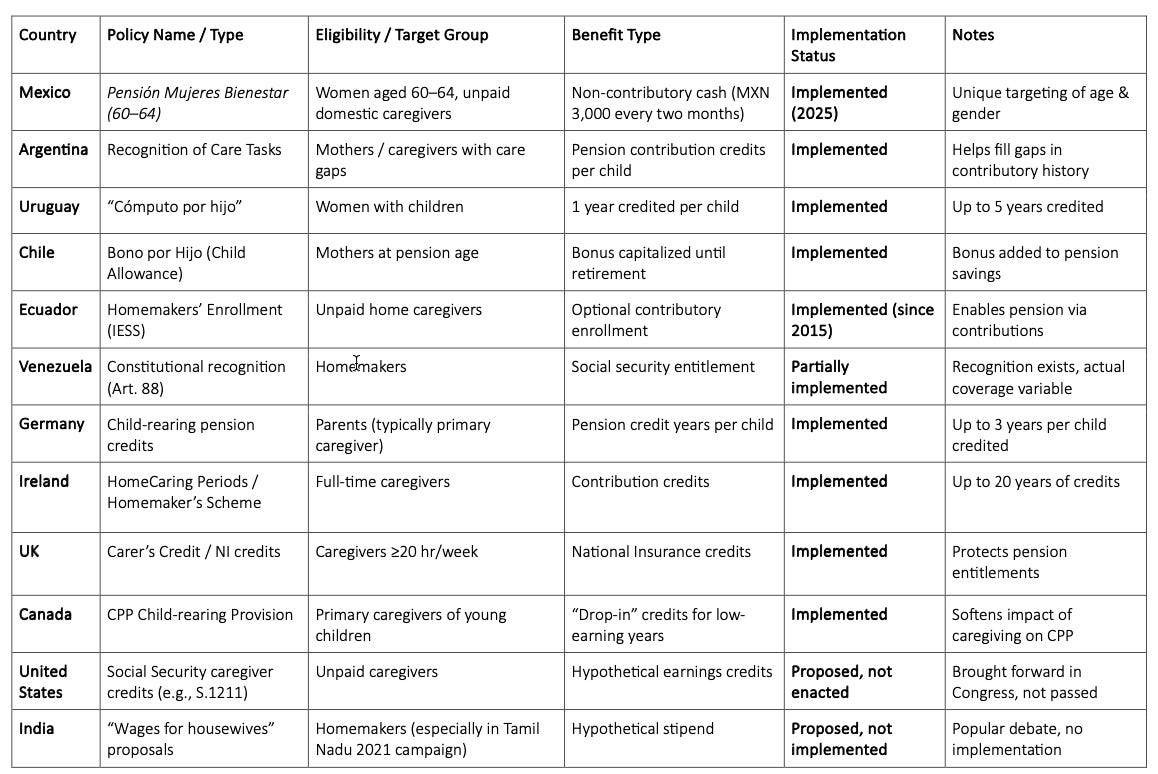

Curious to see whether this was replicated in other countries, I asked ChatGPT to make the neat little table below:

As you can see, recipients vary from women or mothers specifically to caregivers broadly construed. This is not an exhaustive list, but it’s heartening to see the variety of places these policies exist in.

For the last two lines, I asked for examples of countries where caregiving pensions were proposed or discussed, but not implemented.

Unsurprisingly, the US was the first answer. In 2023, Democratic Senator for Connecticut Chris Murphy proposed the Social Security Caregiver Credit Act to “credit certain individuals who provide at least 80 hours of care per month to dependent relatives without monetary compensation with up to five years of deemed wages (...) for purposes of determining their Social Security benefit amounts”. The bill did not go through.

The second unsuccessful example featured, from India, was not a care pension but a ‘wage for housewives’ reminiscent of the original 1970s plea, brought forward by the Makkal Needhi Maiam (People’s Justice Centre) regional party founded by actor Kamal Haasan.

Criticisms of that proposal mirrored those leveraged at the original International Wages for Housework Campaign (IWFHC): no precise specification of how much homemakers would be paid, risk of women being “bullied to take the government’s money and stay home”, worries about exploitation and the lack of labour laws.

These policies, even those that were eventually rejected, are proof some things are shifting when it comes to the economic valuation of care. And it’s important to acknowledge it. Historian Emily Callaci, who wrote a book retracing the story of the original Wages for Housework campaign, gave an interview which states she is “feeling sad that [the movement] got nowhere in practice”. I think the wide range of different care pensions outlined above shows it did get at least somewhere.

Obviously, the Sheinbaum policy and equivalents are not perfect. They aren’t an income, although many of these countries also have caregiver and parental stipends. They’re sometimes gender-specific, begging the perennial dilemma of ‘is it giving long-overdue recognition to women for doing this work or is it perpetuating the idea that care is women’s work and disregarding the fact that many carers are men?’. They maintain a rather strict compartmentalisation of people into ‘workers’ and ‘carers’ with language like ‘care gaps’, which doesn’t reflect the real-life fluidity of care.

But they’re also concrete, implementable and more accessible than broader proposals often dismissed as utopian. Global Women’s Strike, the heir organisation to IWFHC which lives on through the work of Selma James and others, has notably morphed the original plea from ‘wages for housework’ to ‘a care income for all caring work for people and planet’. They call on countries to fairly compensate “all those:

caring for people of every age and condition;

protecting and regenerating the land and the water from poisonous chemicals which ruin the soil, the health of those who work it, the nutritional value of the food, and the climate;

defending human rights and the natural world, risking their lives;

surviving and resisting climate change”.

That’s quite a program. Now, again, the spectrum of change is not zero-sum – I am aware this is more a radical proposal meant to spread ideas about the economic value of care than a point-by-point policy outline with its accompanying budget spreadsheet. But just thinking about the administrative load that would come with identifying, vetting, tracking and monetarily compensating all those who fall under any of the categories above (not to mention the inherent contradictions and slippery-slope risks of people who engage in environmental and human rights activism being completely dependent on their government for their livelihoods) gives me a headache. I’m tempted to whisper: wouldn’t it be easier to just call for UBI?

It seems we often inevitably find ourselves back here. Maybe UBI is to care economics what crabs and trains are to biology and engineering. Of course, the original ‘wages for housework’ campaigners had already reached that conclusion themselves: Selma James favoured a 20-hour working week and a guaranteed income regardless of working status. I assume part of the rationale for calling for a ‘care income’ instead of UBI is its greater efficiency in terms of awareness-raising of the specific value of care work.

One of UBI’s main strengths when it comes to care, though, is its potential for a more flexible distribution of caregiving responsibilities. Take a woman caring full-time for her disabled child: a single ‘wage for housework’ or care pension going exclusively to her risks isolating her in her caring role and strengthening the work/care division. UBI could mean that her partner, less reliant on his salary, could work 4/5ths of the week and take a regular day off to care for their child while his wife gets to pursue other interests, hang out with her friends or work part-time if she so wishes. This is a similar idea to that explored by degrowth scholars like Timothée Parrique, for whom unlocking time for care is one of the key advantages of a reduced emphasis on ‘productive’ labour.

Blueprints, blueprints, blueprints

This is by no means a definitive set of assertions on any of these issues - just some reflections sparked by hopeful news. Sweeping claims when it comes to policymaking are of course to be taken with a sizeable portion of salt, seeing as specific local conditions require tailored approaches. But it remains that moves like Sheinbaum’s – even when imperfect and incremental – provide concrete examples to point to when told ‘it can’t be done’.

Since care is so universal, it is fundamental that those building its futures learn from both ancestral practices and innovative solutions being implemented around the world. The Van Leer Foundation does a fantastic job of spotlighting many of these (thanks Elissa Strauss for introducing me to their work) through their annual journal, Early Childhood Matters.

In their latest issue, you can for example read about how the Nurturing Neighbourhoods initiative is transforming urban spaces in India with ‘pocket parks’ and caregiver-friendly amenities at healthcare centers. You can learn from Ethiopia’s former Minister of Health, Kesete Admasu, about how healthcare policy teams used the traditional coffee ceremony to conduct focus groups with pregnant women and birthing mothers and co-design relaxed, home-like birthing environments tailored to their needs and desires.

In keeping with this global vision, The Fifth Wave will soon be onboarding student ambassadors from universities around the world to help produce a more diverse set of perspectives on care and engage with a wider variety of actors in the space. Stay tuned for team announcements in early November.

For anyone curious to learn more about all things politics, policy and society in Mexico, I recommend Viri Rios’ excellent newsletter Mexico Decoded. Thank you also to Maya Rodale for bringing the Sheinbaum policy to my attention in her post ‘No one wants to do housework’.

All translations and edits mine, apologies for any subtleties lost from the Spanish.

One thing I really like about the Spanish language (this was brought to my attention in a conference by French journalist Lorraine de Foucher) is that it’s much better than French or English at pointing out the real culprit in masculine violence. Spanish-speaking feminists often use “machismo” and “violencia machista” where French typically uses “violences sexistes et sexuelles” and English “gender-based violence” or “violence against women”. But as Foucher pointed out, in ‘violence against women’, the victims are clear, but the cause isn’t. It’s an amorphous epidemic of violence coming from God knows where. Only the Spanish makes the real root - patriarchal masculinity - explicit.

Great essay! Love your international focus.